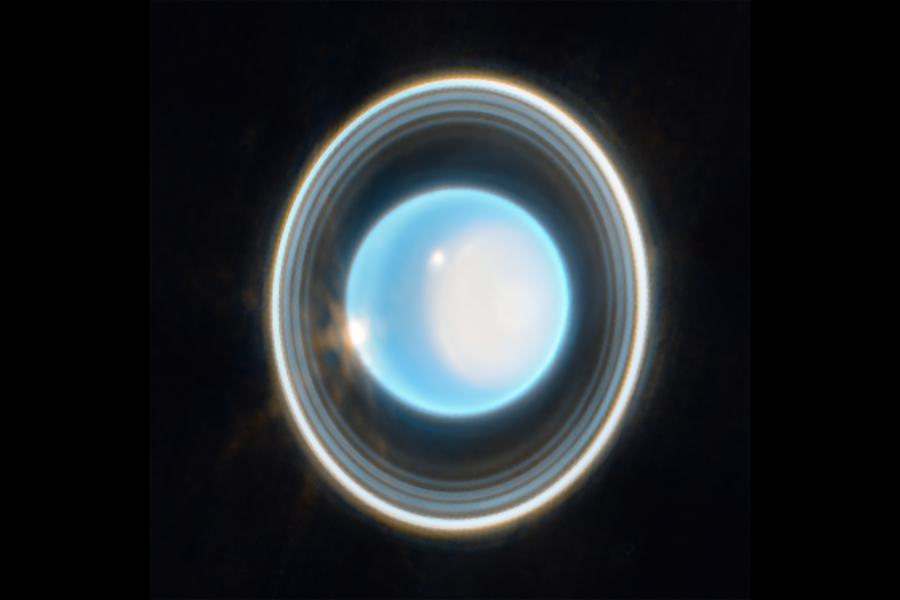

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have unveiled a plan that could significantly reduce the travel time to Uranus, utilizing SpaceX’s Starship. As interest in the ice giant grows, particularly following the 2022 Decadal Survey from the National Academies, the potential for a mission to Uranus is becoming more feasible. The survey identified Uranus as the highest priority destination for exploration within our solar system, yet a fully developed mission remains on the horizon.

Uranus is one of the least explored planets, with the last visit from a probe occurring over 40 years ago when Voyager 2 conducted a flyby. Both Uranus and its neighbor Neptune have never been orbited by a spacecraft, making them unique among the planets in our solar system. The peculiar characteristics of Uranus, including its tilted axis and unusual magnetic field, as well as its moons that may harbor subsurface oceans, present intriguing scientific opportunities.

The distance to Uranus poses significant challenges for any potential mission. Located approximately 19 times farther from the Sun than Earth, it took Voyager 2 more than nine and a half years to reach the icy planet. Previous mission calculations during the decadal survey estimated a travel time of over 13 years to Uranus using a Falcon Heavy booster and multiple gravitational assists. This lengthy duration raises concerns about mission sustainability and funding continuity, especially considering personnel changes and potential budget cuts.

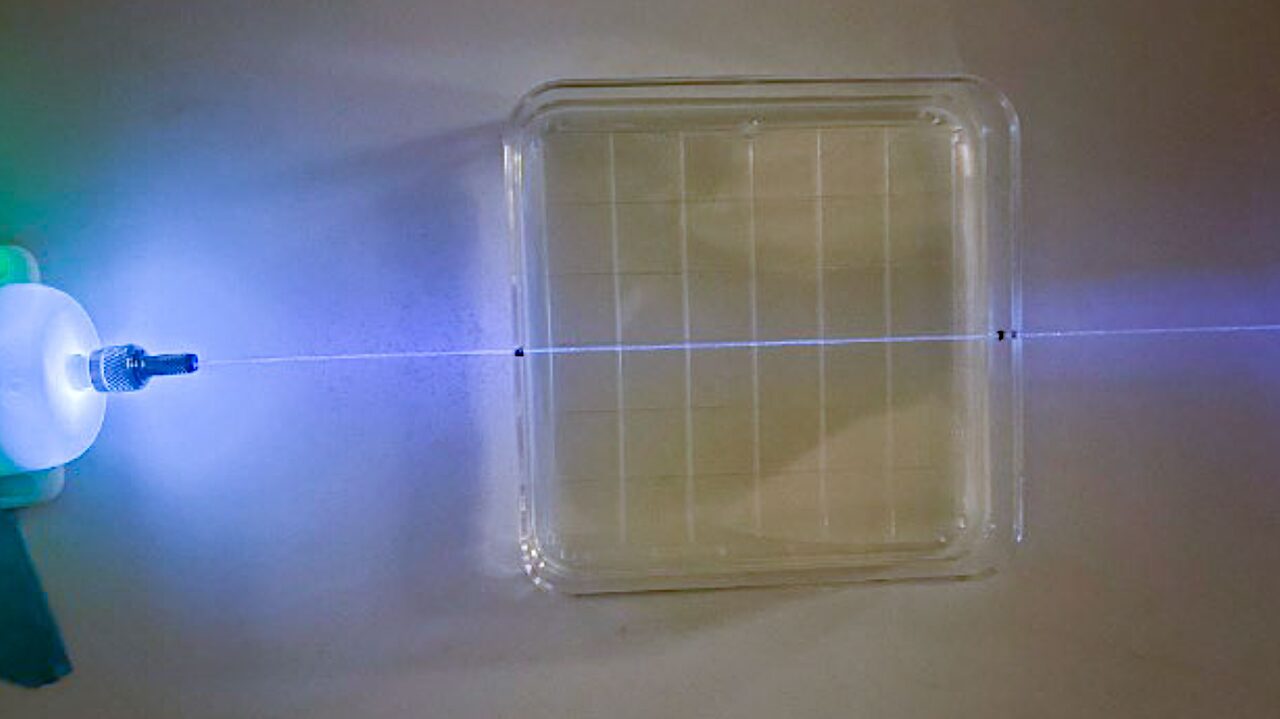

The introduction of the Starship system by SpaceX may change the dynamics of space exploration. Following a series of successful tests, Starship is on track for regular use by the end of the decade, making it a strong candidate for launching the proposed Uranus Orbiter and Probe (UOP). One of the key advantages of Starship is its ability to refuel in orbit. This capability would allow for more efficient fuel management, enabling faster travel to distant destinations.

In their recent paper presented at the IEEE Aerospace Conference, MIT researchers proposed an innovative use of Starship as an aerobraking shield. Instead of detaching from the probe after providing initial thrust, Starship could accompany the UOP to the Uranus system. By utilizing its thermal protection system to slow the probe’s speed during atmospheric entry, they calculated that the travel time could be reduced to just six and a half years. This method also eliminates the need for gravitational assists from other planets, simplifying the mission trajectory.

While this plan presents exciting possibilities, the UOP mission is still in its early stages. The current status of funding for the mission remains uncertain, and given the ongoing challenges at NASA, clarity on the program’s future may not be forthcoming for some time. If the launch windows in the 2030s are missed, the next opportunity would not arise until the mid-2040s, which could mean a gap of nearly 70 years between missions to Uranus.

As researchers and space enthusiasts await further developments, the hope is that agencies responsible for supporting such missions will prioritize exploration of this captivating planet. Whether utilizing Starship or alternative methods, the quest to return to Uranus remains a tantalizing prospect for the scientific community and for our understanding of ice giants in general.