A recent study has provided compelling evidence that a seven-million-year-old fossil, identified as Sahelanthropus tchadensis, was capable of walking upright. This groundbreaking research, conducted by a team of anthropologists, suggests that this ancient species may represent one of the earliest known human ancestors, significantly altering the narrative surrounding human evolution.

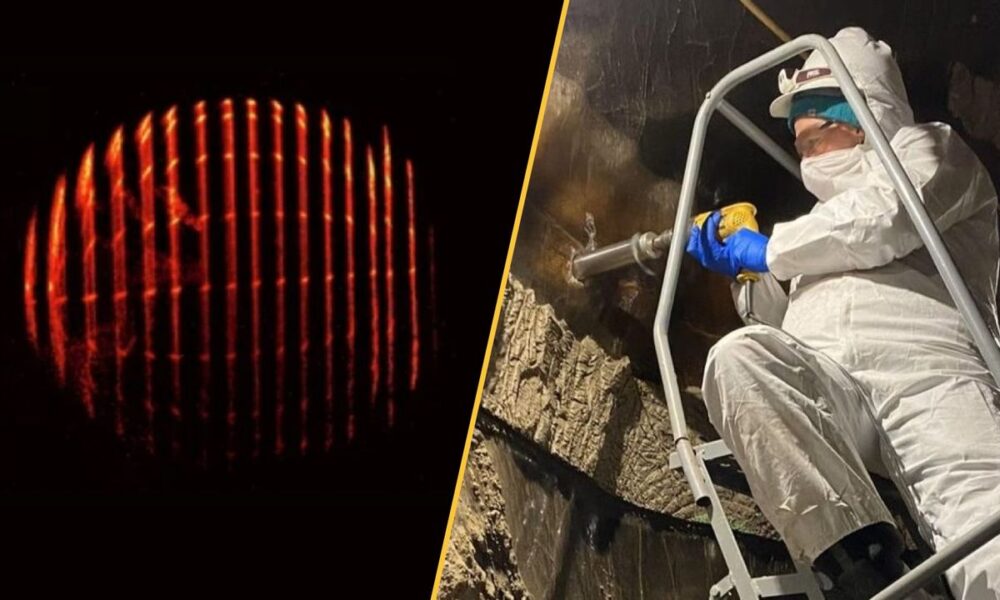

In work published on January 3, 2026, in the journal Science Advances, researchers from New York University and partner institutions utilized advanced 3D imaging techniques to identify key anatomical features in the fossil that support the idea of bipedalism. Among the critical findings is a femoral tubercle, which serves as an attachment point for the iliofemoral ligament, the strongest ligament in the human body essential for upright walking.

Scott Williams, an associate professor in NYU’s Department of Anthropology and lead author of the study, noted, “Sahelanthropus tchadensis was essentially a bipedal ape that possessed a chimpanzee-sized brain and likely spent a significant portion of its time in trees, foraging and seeking safety. Despite its superficial appearance, Sahelanthropus was adapted to using bipedal posture and movement on the ground.”

The fossil was discovered in the Djurab Desert of Chad by a team of paleontologists from the University of Poitiers in the early 2000s. Initial studies focused primarily on the skull, limiting insights into how the species moved. However, recent analyses of additional bones, including ulnae and a femur, reignited the debate about its locomotion capabilities.

Uncovering Bipedal Traits Through Modern Techniques

The study employed a dual methodology, comparing the bones of Sahelanthropus with both extant species and fossil specimens. The researchers utilized 3D geometric morphometrics to analyze bone shape in detail, allowing for precise identification of significant differences that support the hypothesis of bipedal movement.

Three distinct features indicative of upright walking were identified in the fossil. These include femoral antetorsion, the gluteal complex, and the relatively long femur in relation to the ulna. While Sahelanthropus had shorter legs than modern humans, its limb proportions suggested a transition towards bipedal behavior, unlike the typical ape-like structure of long arms and short legs.

Williams remarked, “Our analysis of these fossils offers direct evidence that Sahelanthropus tchadensis could walk on two legs, demonstrating that bipedalism evolved early in our lineage and from an ancestor that looked most similar to today’s chimpanzees and bonobos.”

Collaboration and Funding for Groundbreaking Research

The research team was a collaborative effort involving scientists from the University of Washington, Chaffey College, and the University of Chicago. Additional authors included doctoral students Xue Wang and Jordan Guerra from NYU, as well as Isabella Araiza, who is now a doctoral candidate at the University of Washington. The project received funding from the National Science Foundation.

This new evidence not only sheds light on the capabilities of Sahelanthropus tchadensis but also redefines its place within the human evolutionary lineage. Understanding its locomotion aids in piecing together the complex story of human ancestry, highlighting the intricate pathways leading to modern human bipedalism.